Curtain and Keel

Tommy's Epilogue

The sinking of the Lusitania changed Tommy’s life in ways he could have never imagined. One person made their way into his life and never left. She didn’t leave Queenstown when Tommy was being questioned about the sinking. She was there for him when he needed it.

Cunard Able Seamen

Once the inquiry ended, Tommy made his way north. He had no plans to return to sea, not yet. But he wasn’t ready to leave ships behind either. He found work at Harland and Wolff in Belfast, starting with the heavy labor that others avoided. He did the work without complaint, staying late whenever asked. It wasn’t long before someone noticed.

One of the draughtsmen saw him sketching during a break. Curious, he asked Tommy’s name. There was a pause when he heard the answer. Tommy’s father had once worked in the yard, years before he met Mary (Tommy’s Mother). It didn’t take long for the connection to be made. The draughtsman gave him a chance. Then he gave him a desk.

Over the months that followed, Tommy learned quickly. He asked the right questions and earned quiet respect from those around him. He didn’t talk much about what he was doing, not even in his letters. But by the end of the year, he had his own place in the drawing office.

Katherine came to visit for his birthday in December. She arrived with little warning, holding a paper-wrapped parcel and a smile that said more than words could. They spent a quiet evening walking the edge of the shipyard, talking about the past and pretending the future was already certain. When she left, Tommy returned to his work with a steadier hand.

Tommy entered 1916 with a sense of purpose. He had found his footing at the shipyard, and his work was trusted. When Britannic returned to Belfast in June for conversion back into a passenger liner, he was part of the small team assigned to assist. He had proven himself by then, and for the first time, his name appeared on internal papers. He was not in charge, but his opinion was asked for. And listened to.

The work continued through the summer, until the ship was recalled by the Admiralty in late August. Britannic was once again a hospital ship, and she would be returning to the Mediterranean. When Harland and Wolff was asked to send someone aboard for her next voyage, Tommy was chosen. He was stunned by the decision. There were better men, more experienced ones. But it was his name on the paper.

They gave him every drawing he might need. Onboard, he was shown to a small private cabin. Not much, but more than he expected. He kept to himself, inspecting machinery spaces, checking fittings, watching for any sign of weakness in the ship’s systems. It was her sixth voyage, and by then the routines were familiar to most. But Tommy never relaxed.

When Britannic struck a mine off the coast of Kea, it happened without warning. He stayed calm and moved with purpose, assisting where he could. He managed to get into a lifeboat on the starboard side. From there, he watched the great ship go down.

Only thirty lives were lost. Far fewer than Titanic. But Tommy could not stop thinking about what might have been. How close it came. The sea had tried to take him again. And this time, it had come disguised as the very ship that mirrored the one that took his brother. He returned home quiet. Not broken, but different.

Soon making his way back to Belfast, Tommy found himself unsure of how to carry it all. There was no public inquiry held for Britannic, so he was never called to testify. No statements, no transcripts, no official record. But there were questions. Coworkers asked what it was like, what went wrong, what he saw. He answered only what he had to. The rest he kept to himself.

Back at Harland and Wolff, his tools were where he left them, and his desk sat untouched. But Tommy was not the same. He returned to work, but not with the same rhythm. There were long pauses between lines on the page. His eyes lingered over the shipyard longer than they used to, trailing off toward the water.

Some days he stayed late, not because he had to, but because he did not want to be alone with the silence. Nights were restless. The sound of groaning steel and the tilt of the deck beneath his boots played again in his mind. The flashbacks were brief but sharp. He did not tell Katherine about them.

He tried to keep things steady. He buried himself in revisions and sketches. He visited the draughtsman who had first taken him in, but even that felt different. The work helped, a little. It gave him something to do with his hands when the thoughts got too loud.

Royal Ballet

Katherine’s letters still came from London. She had returned to the Royal Ballet and remained devoted to the company. She wanted to be in Belfast with him. He could see it in her words. But it would mean leaving behind the career she had worked so hard to claim. She was not ready to do that. Not yet. And he did not ask her to.

Instead, he folded each letter carefully and tucked them into the top drawer of his desk. When the workday ended and the yard fell quiet, he would read through them again, one at a time, until the thoughts faded and the world felt steady again.

The war dragged on through 1917. At Harland and Wolff, contracts grew tighter and expectations heavier. Tommy’s responsibilities increased, and he was no longer just another young worker. His understanding of ship design had deepened, and the senior draughtsmen trusted him with more detailed assignments. He spent long hours at his desk, often reviewing modifications or fine-tuning machinery layouts, but his mind wandered. Some nights he stayed late to avoid going home too early.

The past lingered. Britannic was the most recent wound, but not the only one. He had survived the Lusitania and the Halcyon. Each time he had escaped, but the sea always came close. These memories stayed with him. Sometimes it was a flash of panic when a tool clattered. Sometimes it was silence that unsettled him more than noise. He said nothing about it to those at work, but Katherine could tell through his letters.

Katherine was still in London, continuing her work with the Royal Ballet. Though she remained in the background for most productions, she took pride in the discipline and artistry the company demanded. She learned a great deal during this time, but the distance from Tommy wore on her. They wrote each other often. Her letters spoke of costumes, rehearsals, and late nights backstage. His mentioned draughting rooms, wind off the Lough, and men returning from the front. Their visits were brief and difficult to arrange. War travel disrupted every schedule.

In early 1918, a new opportunity arrived. The Grand Opera House in Belfast offered Katherine a position. It did not have the prestige of the Royal Ballet, but it gave her more creative freedom and, more importantly, brought her closer to Tommy. After some thought, she accepted. She packed her things and left London behind.

By spring, Katherine was living in Belfast. Tommy was grateful to share quiet evenings with her. They spoke of the future over tea and modest dinners. She told him about rehearsals and new productions. He showed her the notebooks where he sketched ship ideas that might one day carry his name. Being together gave both of them strength.

Tommy’s ambition grew quietly. He began to consider what it would take to open a small shipyard. The idea was bold, and the odds uncertain, but he knew ships. He had the experience, the discipline, and now the support. Katherine told him she believed in him, even when he doubted himself.

In November 1918, the war finally ended. Bells rang out across Belfast. Crowds poured into the streets in celebration. Tommy stood beside Katherine outside the opera house, watching people cheer as if the weight of the world had lifted. For the first time in years, he allowed himself to imagine a life without war.

The months that followed were difficult. Materials were scarce, and getting anything new off the ground took time. But Tommy had direction. He had purpose. He had Katherine by his side. The world had changed, and they were ready to build something new in it.

The start of the year brought a calm neither had felt in some time. Tommy’s days were filled with blueprints, dockside inspections, and the slow, uphill work of keeping his new shipyard afloat. Katherine’s evenings remained lit by stage lights and soft music, her name printed neatly in programs across Belfast. Between it all, they found each other. Morning walks before rehearsals. Late dinners after long shifts. Letters left on the table. Little things, steady and real.

The shipyard struggled at first. Contracts were scarce, and the postwar economy had not yet settled. Some days, Tommy questioned whether he had moved too quickly. But he refused to give in. He hired who he could, saved what he earned, and built what orders came through. And quietly, the yard began to hold its own. A fishing trawler here. A coastal freighter there. Enough to keep moving forward.

One thing set the yard apart from the rest: Tommy did not care where a man went to church. If you had skill and could work hard, you were welcome. That policy spread fast. In a city still divided by faith, his shipyard stood as neutral ground. Workers showed up from both sides of the line, drawn by fair pay and fair treatment. Tommy never made speeches about it. He just ran his yard with open doors and expected others to do the same.

Katherine’s career kept pace. She remained one of the Grand Opera House’s most admired dancers, and her performances drew full houses. Still, the stage was no longer the center of her life. That place belonged to Tommy now. Their bond grew stronger with each passing season. There was no urgency between them, only certainty.

But Tommy had been planning something all year.

He remembered how, after Lusitania, she had asked to hear him sing. He had brushed it off at the time, too shy to try. But the idea stayed with him. In the quiet hours of spring and summer, he wrote down notes and phrases. Melodies shaped by memory, lyrics drawn from the life they had begun to build. When the song finally came together, he arranged a night she would not forget.

In November, Tommy took her to a quiet lounge. The air was filled with the low hum of conversation and the occasional clink of glassware. A small stage framed by velvet curtains stood at the far end of the room, and when the band stepped into place, Katherine noticed a change in the air. The tune that followed was unfamiliar but somehow intimate.

Tommy stood on stage beneath the warm lights, dressed simply but carrying himself with quiet purpose. The music began softly, a gentle swing with a touch of nostalgia. Then his voice joined in. It was not polished, but it was honest. Every note held weight, and every word seemed written just for her.

He sang of the day they met, of the storm they survived, and how nothing had felt the same since that day in May. The lyrics spoke of more than love. They told a story of healing, of mornings that felt steadier with her in them, of finding comfort in letters and silence and laughter. It was a song filled with their past, but also with a future still taking shape.

Katherine sat still, hands clasped gently in her lap. Her heart rose with every verse. The song ended quietly, not with a flourish, but with a sense of calm. The moment he stepped down from the stage, time seemed to pause. He crossed the floor toward her and reached into his coat pocket.

No speech. No spotlight. Just the ring he had carried with him for weeks, resting in the palm of his hand. Her answer came without hesitation. There was no need for words. It was already written in her eyes.

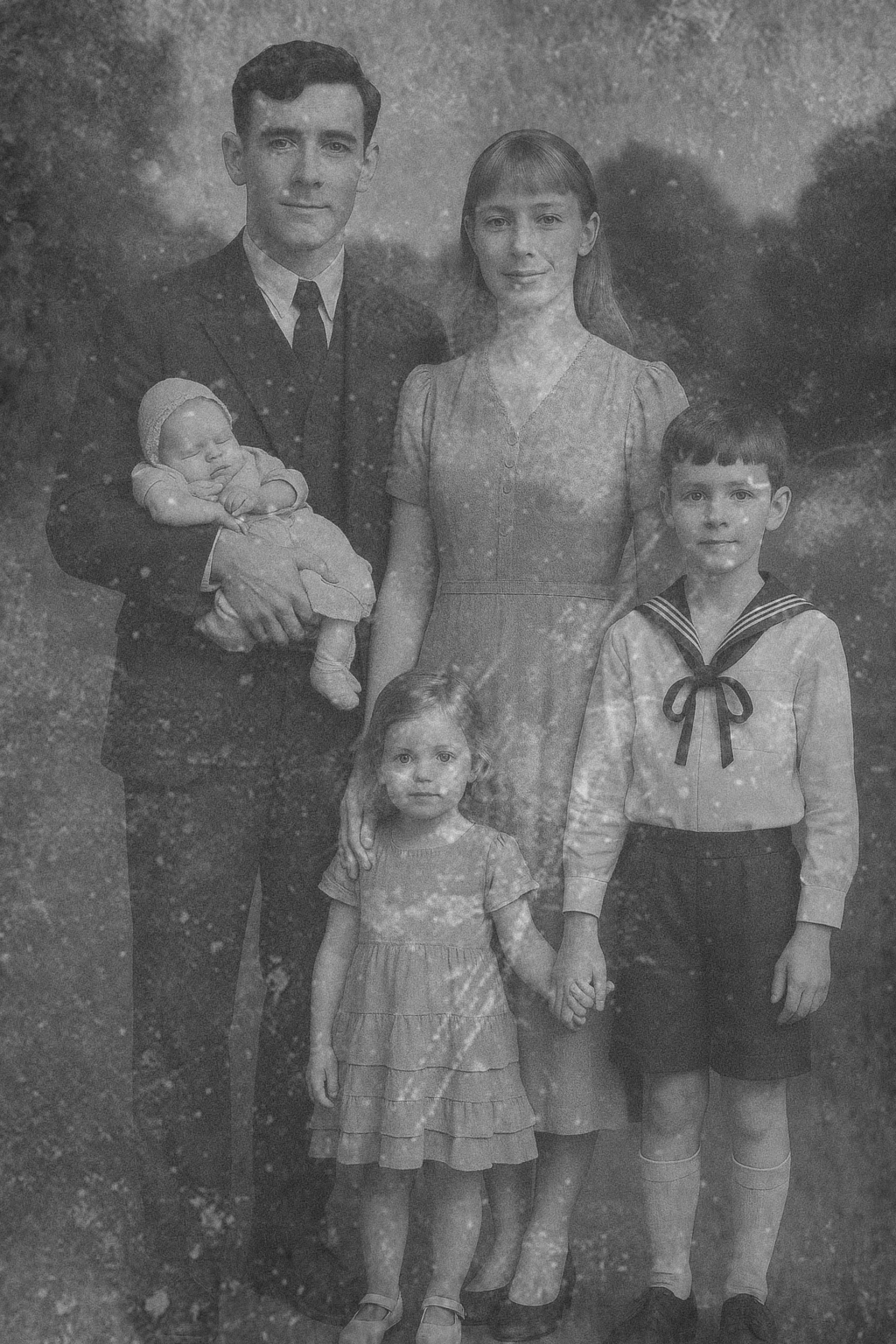

Their wedding took place in December, just before the year came to a close. It was a quiet ceremony, held in Belfast under soft winter skies. The church was modest, filled with friends, colleagues, and a few familiar faces from long before war and distance had taken their toll.

Katherine’s family made the journey north, including her brother Michael, who stood proudly near the front. Tommy’s mother, Mary, came as well, her presence was steady and warm. She had not seen her son so at peace in years, and in the quiet moments before the vows, she held his hand a little longer than usual.

There were no grand gestures, no elaborate decorations. Just music, sunlight filtering through stained glass, and the sound of a promise spoken clearly. For Tommy and Katherine, it was more than enough. As they stepped out into the cold, their hands intertwined, it felt like something long in the making had finally arrived. Not an ending, but a beginning.

The early 1920s brought a different kind of challenge. Belfast was changing quickly, caught in political division, economic strain, and religious tension. Though Tommy and Katherine stayed clear of politics, the unrest shaped daily life in ways they could not ignore. Katherine felt it more than most. Her Catholic background stood out in the Protestant business world, and despite taking the name Greyson, she often found herself treated as an outsider. London had been more forgiving. Belfast, in contrast, reminded her that identity was not something easily set aside.

Her brother Michael visited often. He traveled north not only to see his sister but to press her on the growing movement for Irish unity. Their conversations ranged from gentle to heated. He urged her to speak out more boldly, to use her influence in the north. But Katherine wanted stability. She told him that peace could not be built on slogans alone. The north was fragile. She believed in compromise, not sides. Michael did not always agree, but he respected her for holding firm to what she believed.

Tommy, meanwhile, poured everything he had into building the shipyard he had imagined for years. Progress came slowly. Money was tight, and many potential backers were hesitant. Even with his skill, it took more than hard work to earn their trust. That began to change when Katherine quietly approached her father. It took time to convince him, and even longer to gain full support. Eventually, her family agreed to invest under clear terms. It was not a gesture of faith, but a business arrangement.

Through it all, Katherine stood beside Tommy. She introduced him to people who mattered, arranged meetings, and sat in rooms where few would have expected her. She knew how to carry herself. Her name held weight, and her presence helped Tommy’s yard gain respect. Some were skeptical at first, but her calm voice and quiet confidence made them listen.

By 1922, results began to show. The first ship designed in Tommy’s yard was nearly complete. It was modest by global standards, but the workers took pride in it, and so did Tommy. His designs were clever. His leadership steady. What began as an idea in a worn notebook had taken form in steel and timber, shaped by the hands of those who believed in the work.

Then came the night in 1923. Katherine’s career ended in an instant. A missed step, a sharp pain, and her world shifted. She had torn her Achilles tendon during a performance at the Grand Opera House. The doctors were clear. She would not dance again.

It shook them both. Katherine had loved the stage almost as much as she loved Tommy. He stayed beside her through the long recovery, not offering false hope, only presence. When she finally stood on her feet again, it was not for a performance, but to walk through the shipyard with him, her hand resting lightly on his arm. The future was no longer what either of them had imagined. But it was still theirs to build.

In the months that followed, something shifted between them. The future no longer felt like a distant idea. They had endured loss and change, but they had come through it together. One evening, Tommy quietly said, "Maybe it's time we build something of our own." Katherine didn’t answer right away. She simply smiled, and that was enough.

1929

In 1924, Katherine and Tommy welcomed their first child, a son named William David Greyson. His first name honored Tommy’s grandfather, William Greyson. His middle name was chosen in memory of Tommy’s older brother, David, whose loss remained close to his heart.

Their daughter, Clara Elizabeth Greyson, was born in 1926. Katherine had long admired the name Clara for its simple beauty, while Elizabeth carried a sense of quiet strength and tradition. Clara was observant and thoughtful from a young age, often content to sit and watch the world around her.

In 1929, they had their third child, Lillian Kate Greyson, who quickly became known as Lily. She brought an infectious energy into the household, always ready with a smile or a laugh. Her name reflected a sense of lightness and warmth that fit her perfectly.

Katherine had once considered choosing more Irish-sounding names for the children. Michael encouraged the idea, but Katherine ultimately decided against it, concerned that it might lead to disadvantages later in life. Michael strongly disagreed with her reasoning but accepted her decision and remained supportive.

Throughout these years, Katherine played a vital role in helping Tommy grow his shipyard. She hosted events, built relationships with potential investors, and attended high-society gatherings to strengthen their connections. Her grace and determination opened doors that would have otherwise remained closed.

Tommy poured his energy into the shipyard, spending countless hours refining designs and overseeing the work. Though progress was sometimes slow, their shared efforts gradually earned the company a solid reputation. Their home grew lively with the sounds of children, and their lives, though built on hardship, became something steady and full of hope.

1932

In 1931, an old friend from Katherine’s ballet days invited her back to the stage, this time as a choreography director. With his encouragement, she revived movement for several productions and eventually took the step of directing full performances on her own. Production work proved tougher than dancing had ever been. The theater world was crowded with men who dismissed her ideas, but Katherine was nothing if not persistent. Friends from her performing years spoke on her behalf, giving her a foothold she refused to relinquish. Many nights she arrived home after the children were asleep, tired but invigorated by the chance to shape stories from the other side of the footlights.

In early 1933, Tommy’s shipyard secured its first naval contract. It was a modest deal for two coastal defense vessels, but it opened the door. That same year, Hitler rose to power in Germany. Britain watched with unease, and talk of rearmament began to circulate. The Royal Navy sought builders with fresh ideas and reliable skill. Tommy’s yard was still small compared to the old giants, but his name was gaining attention.

By 1935, everything shifted. A major agreement followed for a new class of fast destroyers, and not long after, the Admiralty placed an order for a light escort carrier. The yard expanded rapidly. New sheds rose along the waterfront, dry docks were lengthened, and the workforce grew quickly, drawing in laborers from Belfast and beyond. Tommy’s designs were efficient and forward-looking. Within a few years, his yard was outperforming firms like Harland and Wolff. While others relied on tradition, Tommy focused on speed, quality, and adaptability.

As more contracts came in, the company acquired two smaller yards: one in Glasgow and one outside Portsmouth. Both were brought up to standard and integrated into the growing operation. The Admiralty no longer viewed Tommy as a promising newcomer. They trusted him. By the end of the decade, his shipyard was delivering new cruisers, fleet support ships, and refined escort vessels at a remarkable pace.

Tommy continued to visit the Belfast yard each morning, greeting foremen and riveters by name. He spent most of his day in meetings and offices, reviewing blueprints and negotiating terms. He worked closely with the Admiralty on refinements and deadlines, taking pride in staying involved at every level of the build.

Back home, life remained centered around family. In 1936, newspapers reported on the remilitarization of the Rhineland. Later that summer, headlines followed the Spanish Civil War. Katherine and Tommy discussed each development with quiet awareness. He understood that new contracts often arrived in the shadow of conflict. Katherine kept directing shows and returned to “Giselle” more than once. She stayed out of politics, but she could feel the mood shifting too.

Despite the tension abroad, the Greyson household remained a steady place. William, now in his early teens, spent hours beside his father’s drafting table. Some days he spoke of running away to sea. Other days he copied hull curves and asked technical questions. Tommy encouraged both impulses. Clara and Lily filled the house with music. Clara favored the piano. Lily played the violin but often slipped away to the shed, watching the shipwrights work with quiet curiosity.

Dinner conversations drifted between William’s drawings, Clara’s upcoming recital, and Lily’s plan to host a concert in the backyard for the shipyard families. Tommy often listened without interrupting, proud of how each child carried forward a part of himself and Katherine. He had added a bomb shelter beneath the garden. It was quiet, hidden under the lawn, but always there. A reminder of what might come.

But not all conversations were light. As the shipyard’s work became more closely tied to Admiralty contracts, tension quietly surfaced within the family. Michael, Katherine’s twin, had spent years engaged in humanitarian work during the Easter Rising and the Irish Civil War. He viewed British involvement in Ireland with lasting suspicion, and the idea of producing warships in Belfast stirred deep unease. Michael urged Katherine to convince Tommy to turn down the naval work, fearing what it symbolized. Katherine listened, understanding his concerns, but felt that the world was moving toward another conflict. Preparations were not just justified but necessary. The ships Tommy was being asked to build would be vital in the years to come. Though the disagreement caused a strain between the twins, they remained close, choosing quiet understanding over division.

By the time war was declared in 1939, Tommy’s shipyard had become one of the most important in Belfast. The Admiralty relied on him not just to build ships, but to help design them. Larger vessels now filled the slips. Cruisers, fleet escorts, and even the early plans for capital ships passed through his team. The Royal Navy trusted him with their biggest risks. He knew it would come at a cost.

In April and May of 1941, Belfast was hit hard during the Belfast Blitz. The city suffered devastating losses, with some of the worst destruction falling near Tommy’s shipyard. Several buildings were flattened in the raid, and production came to a halt. Tommy was devastated by the damage and the lives lost, but he also saw an opportunity. He used the rebuilding process not only to restore operations, but to expand and modernize the yard even further. New facilities were added with reinforced infrastructure, advanced equipment, and improved safety measures. The Royal Navy, recognizing the yard’s growing importance, increased their investment and began awarding Tommy’s firm even more contracts. Some of those contracts had once gone to Harland and Wolff. By the end of 1941, his shipyard was widely considered the most efficient and forward-thinking in the region.

His family was fortunate during the raids. Their home remained intact, and their bomb shelter provided protection when they needed it most. Katherine, fearing for their children's safety, made the difficult decision to have them evacuated for a short time until the danger passed. The separation weighed on both parents, but it gave them peace of mind knowing they were safe.

1942

In 1942, their son William, now of age, made a decision that shook the household. Though exempt from service due to his position at the shipyard, he chose to enlist. He believed in doing his part directly, especially with the war pressing into every corner of Europe. His education qualified him for officer training, and he was placed in the Royal Air Force, where new pilots were desperately needed.

Tommy and Katherine were proud of him, but the worry never left. At first, his letters came regularly, full of optimism and stories of training. Then they slowed. By late 1943, they stopped altogether. The telegram came not long after. William was missing in action and, weeks later, presumed dead.

The news hit hard. Neighbors who had known William since he was a boy were heartbroken. Some left flowers at the Greysons’ doorstep without a word. Others spoke quietly in shops or on the street, saying how they had always liked that boy. They remembered him running through the alleyways or helping with groceries without being asked. A few older men at the shipyard, who had watched him grow up, lowered their heads when they passed Tommy at work, unsure of what to say.

Tommy said little, pouring himself into his work, while Katherine moved through the days in silence. Neither wanted to speak the loss aloud, but everyone in their circle felt it. The light in the house seemed dimmer. The usual warmth behind their front windows was gone.

Just when things seemed their darkest, tragedy struck again. In February 1944, Katherine received word that her brother Michael had been killed during a bombing raid in London. He had been serving in a local church, helping others when the bomb struck. The loss broke something in her. Tommy did everything he could to comfort her, knowing too well what it felt like to lose a brother. He remembered the pain in his mother’s eyes when they lost David. That same look now haunted Katherine’s face. She withdrew into herself for months, barely speaking unless necessary. Even when she began to recover, Tommy could tell she would never quite be the same.

When the war finally came to a close in 1945, it brought with it something neither of them expected. News came through official channels. William had been found alive. He had been held as a prisoner of war in a camp for over two years.

The shock didn’t register right away. Katherine dropped the letter as her hands began to shake. Tommy picked it up and read it again and again, almost afraid to believe it. There were no words at first, just tears and a long embrace in the kitchen where they had once learned he was gone.

The word spread quickly. Neighbors who had mourned quietly now returned with joy. Some wept when they heard, especially those who had lost sons of their own. They remembered the boy who used to race up and down the street or sneak a second biscuit when he thought no one noticed. One woman said she still kept the note William had once written to thank her for lending him a book.

When he stepped off the train, William looked nothing like the boy who left. He was thinner, quieter, and walked with a heaviness that had not been there before. But when he saw his parents, his face shifted slightly and something familiar returned. Tommy and Katherine rushed to him, holding on as if afraid he might slip away again.

They could not reclaim the years they lost, but they found something new in the simple fact that he was home. The family had been broken once, then slowly rebuilt. In the streets of Belfast, where neighbors had shared both grief and hope, the Greysons became a quiet reminder of what it meant to endure.

In the years following the end of the war, life slowly began to take on a new rhythm for the Greyson family. In 1946, Katherine poured herself into her work and debuted her own ballet titled Helenus and Cassandra, a small-cast performance accompanied by a single violinist. The music was based on compositions left behind by her late brother, Michael. Though the show was deeply personal and emotionally moving, it received only modest attention. A few years later, she produced another piece, The Children of Lir, inspired by a Celtic folk tale about siblings turned into swans for centuries. This performance, again dedicated to Michael, was expanded into a full orchestral production and found success with audiences in London, New York, and Toronto. For Katherine, the stage had become a place of both remembrance and healing, and Tommy was always seated proudly in the front row.

While Katherine found her voice again through art, Tommy focused on his son. William returned from the war a different man. The years in the POW camp had left deep wounds, some of which could not be seen. At first, he struggled to find his place. Tommy, recognizing the signs all too well, gave him time, space, and patience. They spent long hours together at the shipyard, not always speaking, but slowly building back trust in the world one task at a time.

In 1948, a turning point came for William. He met someone, and for the first time since the war, allowed himself to feel something close to peace. The relationship grew steadily, giving him a renewed sense of hope and grounding. His sisters, Clara and Lily, were happy for him but remained focused on their own paths for the time being.

In time, William decided to follow in his father’s footsteps. He took a real interest in ship design and engineering, not just out of duty, but because he discovered a passion for the craft. As his confidence grew, so did his influence within the company. Word of his talent began to spread, and before long, the shipyard was receiving new contracts from clients across the country. Many of these were still military in nature, and the shipyard experienced a new wave of growth. The once small operation now rivaled Harland and Wolff in both size and reputation.

Tommy took quiet pride in watching his son flourish. He was proud of all his children, but he saw in William the same drive and sense of purpose he once carried. He knew, without needing to say it aloud, that when the time came to step back, the shipyard would be in good hands.

The start of the 1950s brought new opportunities and personal loss for the Greyson family. In 1950, Tommy was contacted by William Francis Gibbs, the American naval architect heading the design of the SS United States. Gibbs had heard of Tommy’s work and reputation, and invited him to New York for a short consultation. Tommy spent several days reviewing design drafts and offering insight drawn from his experience with fast transatlantic vessels. His contribution was limited but meaningful, and the invitation itself was a mark of respect. It confirmed what many in the industry already knew: Tommy’s shipyard was no longer a modest operation, but a rising force on the international stage. While he was away, William oversaw the yard, managing operations with steady hands and sound judgment. Under his guidance, production remained efficient and deadlines were met with confidence.

Back in Belfast, the shipyard continued to grow. Though wartime demand had slowed, contracts kept coming. There were still occasional builds for the Royal Navy, but the focus had shifted toward modern commercial ships. Tankers, freighters, and a few remaining passenger liners filled the docks. One of the more exciting projects came from Cunard, a welcome commission that stirred old memories for Tommy. The yard's expanding capabilities allowed them to take on larger and more complex vessels, and word of their reliability spread across Europe and beyond. The age of ocean liners was beginning to fade, but Tommy still believed in their elegance and purpose. His shipyard, once considered a small contender, was now shaping the next chapter of maritime design.

In 1952, William married the woman he had met in 1948, a quiet and intelligent woman named Evelyn whom he had grown close to during his recovery years. Their bond had started as friendship, but with time and healing it turned to love. The two were married in a small ceremony attended by family and close friends. By the mid-1950s, they had welcomed their first child, and soon after, another. William balanced his growing family life with his expanding role at the shipyard.

In 1955, Tommy’s mother, Mary Sylvia Greyson, passed away peacefully at the age of ninety-one. Her death marked the end of an era for the family. Tommy often reflected on all that she had endured, from the tragedy that took her husband and children in 1900 and then David in 1912. He had always admired her strength, especially in the years when it was just the two of them. She lived long enough to see Tommy build a family of his own, and to witness the legacy of the Greyson name carried on through her grandson.

Later in the decade, Clara met a young man through her work in the arts. His name was Henry Collins, an up-and-coming actor who had recently started landing roles in television dramas and independent films. He shared Clara’s passion for performance and brought an effortless charm that drew people in both on and off the screen. Their connection grew through rehearsals, late-night script readings, and a shared belief in the power of storytelling. By 1959, they were married in a beautiful ceremony at the Grand Opera House in Belfast. Tommy walked her down the aisle with a bittersweet smile, proud of the woman she had become.

Lily took a little longer to find someone, choosing instead to travel and perform with various dance companies across the UK and Ireland. But late in the decade, she met a stage manager during a tour in Edinburgh. Their connection was instant, and while they weren’t married by the end of the 50s, their relationship was well on its way.

Later that decade, Katherine reunited with Liam Longwood and Natalie Hopewell when dives to the Lusitania wreck began. She supported the site being explored, but objected to large-scale recovery of items from the ship. One exception was made when a diver found a violin preserved in its case near the remains of her and Michael’s cabin. Katherine immediately recognized it as Michael’s and kept it as a deeply personal reminder of him. She placed it in their home with quiet reverence.

News that Lusitania may have carried munitions disturbed her. She wondered if any of those weapons had come from her own family’s business connections during the war. Though she kept those thoughts to herself, she was quietly relieved that Michael had not lived to hear about such findings.

Through these years, the Greyson family remained close. Tommy continued to support Katherine’s creative pursuits, while guiding William in his growing leadership role. The shipyard stayed strong, and life carried on with its usual rhythm, shaped by both memory and hope for what came next.

Tommy’s shipyard remained highly successful throughout the 60's. Postwar demand for reliable vessels kept work steady, and the company’s reputation continued to rise. Tommy, now in his seventies, began to gradually step back from most responsibilities. He allowed William to take on more leadership, offering advice when needed but trusting his son to carry on the family’s legacy. By the end of the decade, William was in full control of the shipyard, and Tommy was content to watch his son lead.

William continued to balance work and family with quiet confidence. He and Evelyn welcomed a third child in the early 1960s, and their home was often filled with laughter, muddy shoes, and the smells of fresh bread and machine oil. Despite his growing responsibilities, William never let the shipyard pull him entirely away from family life. He spent most evenings at home and made a point to attend school recitals and Sunday dinners. His leadership style mirrored his father’s: measured, humble, and always hands-on.

During this period, Harland and Wolff began scaling back its broader operations. Several of their other shipyards outside Belfast were closed, and the company chose to focus its efforts solely on its Belfast facilities. This shift opened up new opportunities for Tommy’s company, which continued expanding both its workforce and production capacity. New contracts came in not just from the Royal Navy but also from private firms and foreign governments. Tommy’s company continued expanding, not just in new naval and merchant contracts but also through strategic investments, including a small steel-fabrication plant in Scotland by the late 1960s. Belfast quietly glanced at the Greyson yard as the future of Northern Irish shipbuilding.

For Clara, she had fully embraced her role as a mother and wife, raising two children with her husband, Henry Collins. She remained involved in the theater world, though she spent more time behind the scenes than on stage. Occasionally, she worked alongside Katherine to coordinate outreach programs and kept close ties with the Grand Opera House. She helped organize events, mentored younger performers, and ensured the values she and her family cherished continued through the next generation.

In 1964, Lily surprised the family when she announced her engagement to Ian Callahan, a stage manager she had met during a tour nearly a decade earlier. They were married that summer in a modest ceremony surrounded by close friends and family. Lily continued to perform occasionally but shifted her focus toward teaching dance to children and choreographing local productions. She and Ian remained based in Edinburgh, though they visited Belfast often.

Katherine remained connected to the theater, although she began to slow down. In the early part of the decade, she stepped away from producing shows but continued to support the arts. She donated to programs that helped children from working-class neighborhoods in Belfast gain access to theater and music. Katherine believed that the arts could help bridge divides within the city and pushed for the Grand Opera House to become a place for unity and shared culture. As the years went on, however, her memory began to fade.

In 1967, Katherine was diagnosed with dementia at the age of seventy-five. Though her memory began to fade, she still remembered the music, the rhythm of dance, and her brother Michael. Tommy stayed close, taking on the role of caregiver with quiet devotion. He no longer spent full days at the shipyard, choosing instead to focus on her needs. Their daughter Clara helped when she could, but it was Tommy who remained by Katherine’s side each day, offering the same steady presence he always had.

Throughout the 1970s, Katherine’s health continued to decline. She was no longer able to take part in the theater, but her influence remained. The Grand Opera House and the scholarship she helped create continued to support young women in the arts. Family visited often, and Clara stayed nearby to assist. Tommy never left her for long. Even as her memory faded, the bond between them stayed strong, shaped by years of love, patience, and all they had built together.

Katherine passed away in 1977 at the age of eighty-one. She was surrounded by her family when she died. Her final words were barely audible, but those present believed she saw Michael coming to guide her home. The family held on to that image, choosing to believe that brother and sister were reunited at last.

Her death broke Tommy in a way that words could not fully explain. Though he had survived loss before, losing Katherine was like losing the other half of himself. In the quiet that followed, he would often sit with old photographs or hum the melody of the song he once wrote for her. He continued living for the sake of his children and grandchildren, but something had gone still inside him.

Clara, now a mother of two and deeply involved in both her family and the local arts community, took comfort in preserving her mother’s legacy. She remained active in coordinating scholarship recipients and mentoring young performers. Her husband, Henry Collins, stood by her through the difficult years, offering quiet strength.

William, still leading the shipyard, balanced the demands of business with the responsibilities of fatherhood. His children were growing older now, two of them already in apprenticeships and one showing early promise in architecture. Though William rarely spoke of his feelings, his love for his parents was reflected in the way he ran the yard, with integrity, care, and an unwavering commitment to people.

Lily had settled into a peaceful life in Edinburgh with her husband Ian and their two daughters. She continued to teach dance and occasionally visited Belfast for family gatherings, always arriving with a burst of warmth and laughter that lifted everyone’s spirits. Though she was farther away, her bond with her parents and siblings never wavered.

In 1979, just two years after her passing, Tommy died peacefully at home. His family was with him in his final hours. His last words were simple, but deeply felt: “I’ve only ever loved one way.” It was the final line of the song he had written the night he asked Katherine to be his wife.

After his passing, tributes came in from across the country. Colleagues in the shipbuilding world remembered him as a man of quiet brilliance and unwavering integrity. Those in the theater remembered the way he supported Katherine with pride and sincerity. In Belfast, the Greyson name came to be associated with strength, compassion, and perseverance.

The shipyard continued under William’s leadership, guided by the lessons Tommy had passed down. Under William, the business remained one of the most respected yards in the country. Its focus broadened to include modern naval designs, advanced cargo vessels, and even collaborative research into fuel-efficient maritime technologies. The yard became a source of stable employment for generations of workers, many of whom spoke of the Greysons not just as employers but as a family.

The scholarship in Katherine’s name expanded, offering opportunities to young artists in need of support. Their children and grandchildren carried on their legacy, each in their own way. And in the hearts of all who knew them, Tommy and Katherine remained side by side, remembered not only for what they built, but for how deeply they loved.